Actual Place of Diuretics in Hypertension Treatment-Juniper Publishers

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS-OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL OF CARDIOLOGY & CARDIOVASCULAR THERAPY

Abstract

Diuretics represent a large and heterogeneous class

of drugs, differing from each other by structure, site and mechanism of

action. Diuretics are widely used, and have several indications in

different cardiovascular disorders, particularly in hypertension and

heart failure.

Despite the large number of available

anti-hypertensive drugs, diuretics remained a cornerstone of

hypertension treatment. In the current editorial, we assessed the actual

place of different diuretics in the hypertension guidelines focusing on

the concept of tailored approach in prescribing them for hypertensive

patients.

Introduction

Diuretics represent a large and heterogeneous class

of drugs, differing from each other by structure, site and mechanism of

action. Diuretics are widely used, and have several indications in

different cardiovascular disorders, particularly in hypertension and

heart failure.

Despite the large number of available

anti-hypertensive drugs, diuretics remained a cornerstone of

hypertension treatment [1]. Indeed, they are the second most commonly

prescribed class of antihypertensive medication. For instance, 12% of US

adults were prescribed a diuretic, and the relative increase in

prescriptions from 1999 through 2012 was 1.4 [2]. However, a question

remains looking for an answer: which diuretic for which hypertensive

patient?

The overall action of diuretics (except osmotic

diuretics) can be summarized as the blockage of sodium reabsorption at

the nephron major sites leading to an increase in water excretion.

Figure 1 illustrates the sites of action of different diuretic agents;

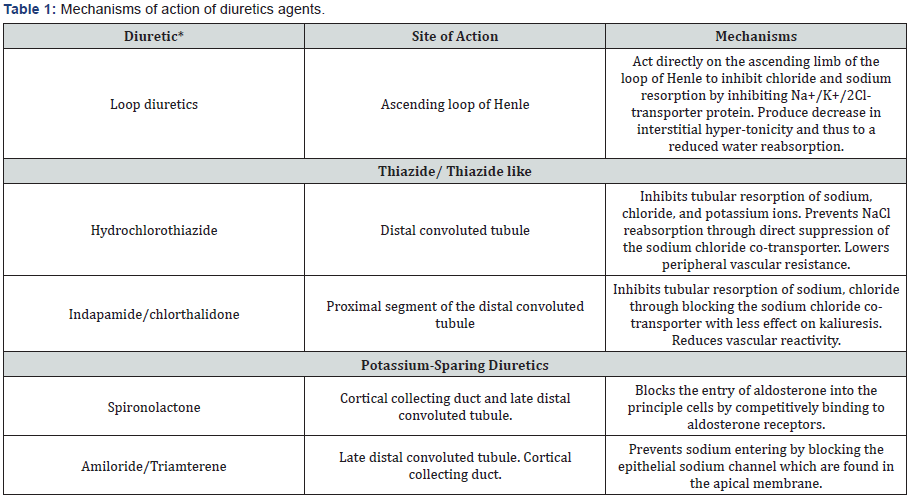

Table 1 describes their mechanisms of action.

a: Osmotic diuretics; b: Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors; c: Loop

diuretics: d: Indapamide & Chlorthalidone; e: Hydrochlorothiazide; f:

Amiloride & Triamterene; i: Spironolactone.

ALoH: Ascending Loop of Henle; BC: Bowman Capsule; CD:

Collecting Duct; DCT: Distal Convoluted Tubule; DLoH: Descending

Loop of Henle; PCT: Proximal Convoluted Tubule

*Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and osmotic diuretics are not included.

In addition to their nephrogenic effects, some diuretics

according to their structural proprieties can lower blood

pressure via other pathways. For instance, indapamide has

calcium antagonist-like vasorelaxant effects that strengthen

its lowering blood pressure action [3]. Spironolactone likewise

has another site of action on arterioles receptors, where it

antagonizes aldosterone-induced vasoconstriction, resulting in

diastolic and mean pressure reduction [4].

Nonetheless, the most worrying adverse effects of this class

of agents is electrolytes derangement. Serum potassium level

may be lowered by thiazides and loop diuretics and elevated by

aldosterone antagonists. Hyponatremia is more common with

chlorthaliadone than hydrochlorthiazide but not at equipotent

doses and the incidence of hyponatremia for both medications is

very strongly age related [5].

Formerly, diuretics were considered to be one of the most

effective antihypertensive treatments. Nowadays, after the onset

of new potent anti-hypertensive drugs, diuretics may be no

longer considered the most privileged first-line strategy [6,7].

Indeed, most of the current guidelines downgraded the place

of thiazide diuretics in the management of hypertension from

the preferential initial therapy to one of the possible first-line

alternatives among a large armamentarium of anti-hypertensive

drugs [8-12].

The recent Australian guidelines emphasize that the choice

of a drug to initiate or to maintain an anti-hypertensive therapy

should consider several parameters: patient’s age, race, comorbidities,

potential interaction with other drugs, cost,

patient’s choice and implication for adherence [12]. Hence,

these guidelines suggest to the practitioner 4 or 5 different class

drugs, giving him the freedom to choose the most suitable drug

for each patient as a personalized treatment approach.

Among the diuretics, thiazide and thiazide like diuretics

are those recommended as first-line strategy for primary

hypertensive treatment in different guidelines [8-12]. Table

2 summarized the evolution of the place given to diuretics in

hypertension treatment in different guidelines.

CHEP: Canadian Hypertension Education Program; ESC: European

Society of Cardiology; JNC8: The Eighth Joint National Committee;

NHFA: National Heart Foundation of Australia, NICE: National Institute

for Health and Clinical Excellence; WHO: World Health Organization.

Thiazide diuretics are privileged as the appropriate option in

a variety of circumstances like for salt sensitive patients (such as

black patients) and for those elderly with systolic hypertension

[13]. In other clinical scenarios, they can be prescribed as one of

5 first-line antihypertensive alternatives [8-12].

However, other types of diuretics are barely mentioned

in different guidelines and thereby are underutilized in daily

practice [1]. Table 3 summarized the ideal clinical indications of

each diuretic.

Thiazide and thiazide like diuretics do not have the same

structure neither the same site of action, and that would explain

the huge disparities concerning their efficiency and side effects.

Despite their differences, the recommendations generally

do not favor any agent on the other [8-11]. Indeed, although

recommendations encouraged a treatment approach based on

considering patient’s characteristics, the majority of guidelines

are based on evidence for drug classes rather than individual

drugs. Only Australian guidelines encourage when initiating or

changing treatment, to prescribe a thiazide-like diuretic, such

as chlorthalidone or indapamide in preference to a conventional

thiazide diuretics [12].

Hydrochlorothiazide: Much evidence support the inferiority

of hydrochlorothiazide compared to other thiazide like agents

[1]. In fact, hydrochlorothiazide duration of antihypertensive

action is less than 24hour, while indapamide has even in the

immediate release form, at least 24-hour duration of action for

blood pressure reduction [14]. Duration of action is important

in view of the fact that targeting nighttime blood pressure may

reduce cardiovascular events [1]. Hydrochlorothiazide is also

less potent than converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin

receptor blockers, beta-blockers, and calcium channel blockers.

In a network analysis, hydrochlorothiazide alone was

shown to be less effective in preventing cardiovascular events

in comparison with chlorthalidone and the association

hydrochlorothiazide-amiloride [15]. Furthermore, it is

inferior to indapamide in improving endothelial function and

longitudinal strain in patients with hypertension and diabetes [16]. Hydrochlorothiazide is also inferior to spironolactone in

improving coronary flow reserve [17].

The only advantage of hydrochlorothiazide over both

chlorthalidone and indapamide seems to be it extensive

availability in formulations with other classes of antihypertensive

drugs and his low price.

Indapamide: Many authors suggest that indapamide is by far

the most efficient and tolerable diuretic for hypertensive patients

[8]. Compared to hydrochlorothiazide, it was demonstrated to

be more efficient in improving micro-albuminuria (in diabetics),

reducing left ventricular mass index, inhibiting platelet

aggregation, and reducing oxidative stress. Indapamide also

proved its capacity to reduce left ventricular hypertrophy more

than enalapril [18].

Another important feature, is that indapamide do not share

with thiazide diuretics their adverse effects on lipid and glucide

metabolism, thereby it can safely prescribed in diabetics patient

[1].

Indapamide or chlorthalidone: The choice between

indapamide and chlorthalidone is quite a relevant question. But

the main obstacle that is faced to answer to this question is that

there is no trial through literature that compares chlorthalidone

and indapamide in the literature.

Kaplan [19] suggests that the choice between these 2

efficient drugs should be based on the 3 following criteria: (i)

the ease of use; (ii) the cost; and (iii) hypokalemia which is a

considerable drawback of chlorthalidone [8]. Indeed, the fall in

serum potassium with 12.5mg doses of chlorthalidone is nearby

0.1mmol/L greater than that seen with equivalent doses of

hydrochlorothiazide [1].

The huge disparities of thiazides prescription may be due

to that chlorthalidone is only commercialized with atenolol

and azilsartan. Likewise, Indapamide is only combined with

perindopril.

Both observational and randomized trials have shown that

thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics (generally at higher doses)

can cause ventricular ectopy and sudden death [1]; the addition

of potassium-sparing diuretics might prevent it [20].

Furthermore, in elderly hypertensive patients, both amiloride

and triamterene were showed to be efficient when combined to

hydrochlorothiazide to reduce cardiovascular events compared

to placebo [21]. While spironolactone did not show appropriate

evidence for reducing cardiovascular events in hypertensive

patients, its place in reducing total mortality in advanced heart

failure is well known [22]. Moreover, its efficiency in resistant

hypertension is well established [23].

Spironalctone has several others non blood pressure

benefits like reducing proteinuria by 61% in proteinuric kidney disease, albuminuria by 60% in type 1 diabetes, and normalizing

left ventricular hypertrophy in primary aldosteronism and low

renin hypertension [1].

Both spironalactone and eplerenone are indicated in patients

affected by heart failure. Although resulting in similar rates of

hyperkalemia, eplerenone was shown to have greater impact on

systolic blood pressure and to improve endothelial function in

hypertensive patients [24,25].

Loop diuretics are mostly indicated as an alternative to

thiazide diuretics in case of chronic kidney disease with serum

creatinine is >1.5mg/dL or eGFR is <30mL/min/1.73m² [1].

The antihypertensive effect of low-dose loop diuretics could be

improved with nighttime administration.

Diuretics are a popular, heterogenous class of antihypertensive

drugs with several decades of clinical application. The concept to

replace “one size fits all” paradigm to a more tailored approach

in prescribing diuretics to hypertensive patients seems to be

rational and appropriate for a better clinical benefit.

For more articles in Open Access Journal of

Cardiology & Cardiovascular Therapy please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/jocct/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment