A Detailed Checklist in Cardio-Thoracic Surgery: The Isala safety Check-Juniper Publishers

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS-OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL OF CARDIOLOGY & CARDIOVASCULAR THERAPY

In various fields of complex environments,

checklists have been introduced, mainly to improve procedural related

aspects like logistics, personnel support and equipment. However, in

order to pursue better outcome, major patient-related factors may be

likewise important to check immediately before surgical procedures.

Therefore, a specific checklist, the Isala Safety Check, was developed

in a high-volume cardio-thoracic surgery unit. It concerns a short list

focusing on the presence of potential sources for peri-operative

complications, including actual information of cardiac function,

pulmonary comorbidities, renal impairment, neurological condition,

predisposing factors for postoperative infections and risk of

transfusion. Special attention is paid to the on-site information

obtained by standard transesophageal echo, particularly the

visualization of the condition of the ascending aorta. After anesthesia

induction, but just before skin incision, these items are discussed in

the presence of the entire team, by means of a checklist. Consensus is

achieved to whether there are any adaptations required for the

operation. This method has shown to increase team awareness, stimulate

communication and may improve outcome. Details of the Isala Safety Check

and the application of this checklist in routine and emergency cardiac

surgery are discussed.

Abbreviations: TEE: Transesophageal Echo; WHO: World Health Organization; GFR: Glomerular Filtration Rate

Introduction

Careful pre-procedural evaluation of patients is one

of the cornerstones of preventing complications in many complex

procedures, including cardio-thoracic surgery. A stop moment, like the

time-out immediately before surgery, has demonstrated its importance and

has become routine in many complex team-driven specialties, in medical

and non-medical surroundings [1]. In addition, several specific

checklists have been developed, and proved highly effective in

decreasing complications [2]. However, for cardio-thoracic surgery

patients important items are not addressed during a standardized

time-out. Also, time-out checklists focus primarily on procedural issues

and still lack optimal communication about patient specific risk

factors between the team members before incision [2]. This of interest,

because the current guidelines provide only a few recommendations of

evaluating patients for cardio thoracic surgery [3]. Although our unit

has established good outcome results over many years, we developed an

extended checklist. This is based on the fact that a substantial number

of cardiac surgery related deaths is avoidable [4]. Introducing a

specific checklist, by professionals and intended for professionals,

covering patient-specific items with respect to risk factors for

perioperative complications, we assumed to improve patient-related

outcome and team performance [5]. The checked items are discussed just

before skin incision, because at this moment all information is

up-to-date and complete, including standard pre-procedural

transesophageal echo (TEE), and there is still an opportunity to adapt

the surgical strategy. Details of the Isala Safety Check, backgrounds

and suggestions for implementation are discussed in this paper.

The routine pre-operative assessment of cardiac patients for

non-cardiac surgery is well studied and described [6]. However,

there is limited literature on the content of a structured

routine pre-operative evaluation of patients for cardiothoracic

surgery. Furthermore, although the guidelines give only few

recommendations, particularly on pulmonary and renal function,

a structured approach to a complete pre-operative evaluation is

lacking and therefore may be variable [3].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed

a surgical safety checklist in 2005. This checklist has found

wide adoption and is now used in all fields of surgery even in

minimal invasive procedures [7]. Since 2009, a standard timeout

procedure is mandatory in all Dutch hospitals for every

surgical intervention [8]. The checklist for this procedure is

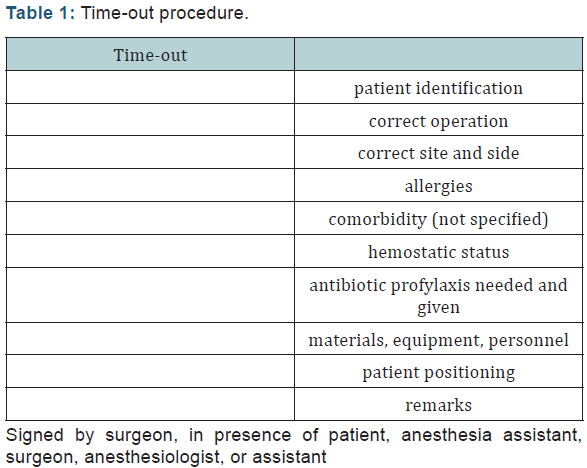

summarized in (Table 1). This checklist focuses on procedural aspects. Checking these items minimizes wrong patient/

procedure/site complications and prevents intra-operative

delay due to equipment problems. The time-out procedure has

proven its effectiveness in the field of mixed surgical population,

general surgery, orthopedic surgery, otorhinolaryngology and

neurosurgery [9-11]. Despite a few negative reports [12], a

significant reduction was demonstrated in overall complication

rate and even in mortality [13]. In the SURPASS study, the WHO

checklist was extended to a multistage, multidiscipline document

covering the entire patient course from admission to discharge.

This approach reduced in hospital mortality from 1.5 to 0.8%

and total complication rate from 27.3 to 16.7% [2].

Although the WHO surgical checklist reduced both

complication rate and mortality, there are some limitations of

this approach. Whereas it focuses on the procedural aspects,

communication on patient information concerning risk factors

and comorbidity might receive little attention. Furthermore,

a checklist on itself does not require interaction or discussion

[14]. Therefore, there is a possibility that after the first

introduction of a checklist the behavior of the performing team

changes into a “ticking” culture instead of actual awareness and

concern for the situation [15]. In Ontario, the introduction of the

surgical safety checklist has not led to a measurable change in

outcome [12]. One of the reasons might have been that, besides

the short period of evaluation, the standard checklist is not

directly calling for actions by all members of the operating team

[16]. Finally, the surgical safety checklist is, by design, a general

checklist. This implies that items concerning a specific type of

operation or patient category are lacking. Therefore, checklists

especially designed for certain operations, like transphenoidal

neurosurgery, were developed [17-18]. Cardiac surgery is also

such a type of operation, with specific risk factors and a patient

population with extensive comorbidity, requiring a specific

cardiac surgery checklist.

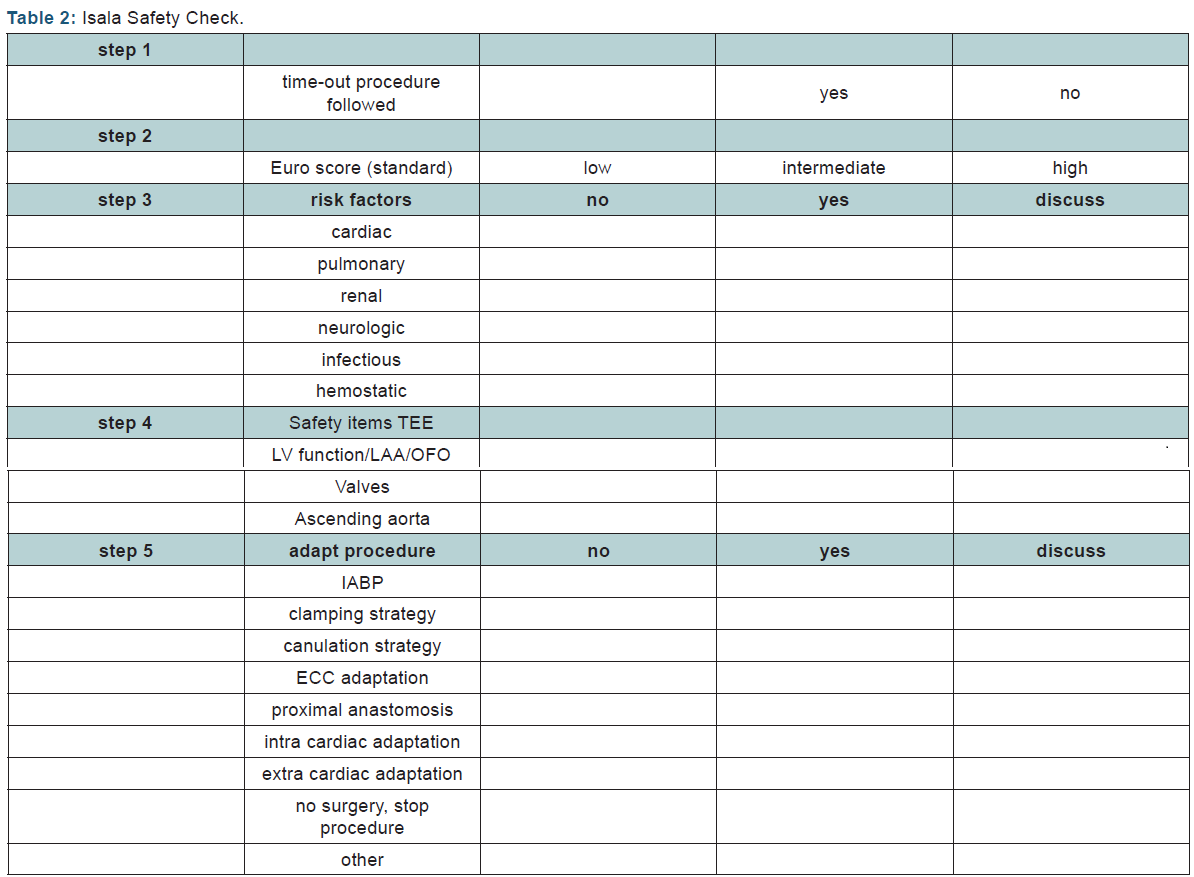

The items that are checked are represented in (Table 2).

It is essential that the total procedure is done by the complete

team, comprising the cardiac surgeon, the assisting, scrub

nurse, anesthesiologist, anesthetic nurse and perfusionist. The

first checked item by the team is whether the regular time-out

was indeed performed. If the regular time-out procedure was

not performed, the surgeon is urged to perform. Especially in

the setting of life threatening emergency cases this step might

have been skipped initially but should be performed at this

moment, or it should be documented that the team decides

that the regular time-out cannot be performed. To increase

the awareness for every team member with regard to the

expected mortality of the procedure, the calculated EuroSCORE

is repeated. Accordingly, patients are divided into three groups:

low, intermediate and high risk [19]. The third step is to identify

other specific peri- and postoperative risks and complications

with focus on six main organ specific topics: cardiac, pulmonary,

renal, neurologic, inflammation and coagulation. Cardiac risk

factors include reduced ventricular function, hypertrophy,

critical coronary artery stenosis, intra-cardiac shunts, valvular

dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension. Each of these findings

may require additional measures.

Pulmonary risk factors include mainly COPD, bronchiectasis

and restrictive pulmonary function. These conditions may urge to

reduce tidal volume, focusing on lung protective ventilation and

careful fluid balance [20]. Increased risk for renal dysfunction

may arise from an already decreased glomerular filtration rate

(GFR), but also previous periods of (reversible) renal failure.

Anticipation may involve the use of additional filtration on the

extracorporeal circuit or targeted perfusion pressure [21]. It

may be indicated that postoperative strategies are discussed

here already. Factors that lead to a higher risk of adverse

neurologic outcome are discussed. Previous stroke, transient

ischemic attacks and known carotid artery stenosis are the most

prominent factors. Preventive measures may include higher

perfusion pressures, additional monitoring of the ascending

aorta and postoperative anticoagulant therapy. Conditions that

increased the risk of infectious complications are discussed, like diabetes, depressed immune system, urinary tract problems or

chronic pulmonary disease. Special attention is paid to the risk

factors for postoperative wound infection. Preventive measures

include avoidance of bilateral mammalian artery use and

continued use of antibiotics postoperatively. Cardiac surgery

interferes with the hemostatic system and patients are mostly on

anti-coagulant therapy. Careful discussion on the management

of this therapy is mandatory. Therefore, the risk factors for

hemostatic complications and possible preventive measures are

to be discussed.

The fourth step of the Isala Safety check consists of

information from actual transesophageal echocardiography

(TEE) images, obtained immediately after induction of anesthesia.

The required images include a stepwise identification of global

myocardial contractility, possible sources of intra-cardiac

emboli, the oval foramen, all cardiac valves and the ascending

aorta. If any atherosclerosis with a grade of 3 or more based on

the Katz classification [22] of the visible part of the ascending

aorta or descending aorta is found, additional imaging of the

ascending aorta using modified TEE [23] should be considered

in order to increase the diagnostic accuracy of TEE [24]. The

results of this so-called focused TEE investigation are discussed

within the team. The fifth and final step is to summarize and

discuss the findings of the first steps, and decide whether an

adaptation of the surgical plan is necessary. This can vary from

additional monitoring by epi-aortic scanning in order to guide

changes in the canulation or clamping site, or to a total change

in surgical approach, as example change from on-pump CABG to

off-pump CABG.

The Isala Safety check is performed after induction of

anesthesia, just prior to skin incision. This moment is chosen

because at this time all information is available, whereas there

is still a possibility to change the strategy for the operation and

even to stop the operation. It is essential that all members of the

team are present, including perfusionist, scrub nurse, surgical

assistant, anesthetic nurse, surgeon and anesthesiologist. The anesthesiologist is in the lead together with the surgeon in

communicating about the safety check items. Since all activities

are paused during the checklist maximum awareness is ensured.

Most patients have elective surgery, and in these patients the

Isala Safety check can be performed, with minimal time loss. A

YouTube demonstration has shown that the team communication

will take only 2.09 min and no additional operative time is needed

to obtain the specific TEE images. Although the Isala Safety

Check is primarily designed for elective surgery, emergent cases

may benefit even more, particularly because most complications

occur in emergent cases. Monitoring the results of the Isala

Safety check, by registering adaptations to the operation plan in

combination with outcome of surgery, creates a feedback loop.

Regular update of this information to the healthcare providers

may lead to better preparation of patients and a tapered workup

for specific groups of patients.

The first potential limitation is time loss, due to both

numerating the comorbidity of the patient and the assessment of

a dedicated TEE examination. However, all items addressed in the

Isala Safety Checklist are notified information in the patient file

and the TEE is a focused examination that is performed during

the surgical preparation phase with no increase of operative

time. The second limitation is that the Safety Check is performed

just before skin incision, being late in the entire work-up process.

Changing the operation procedure or even stop the procedure at

this moment will have major (emotional, logistic and financial)

effects. However, this is the final moment to prevent major

complications and a sub-optimal approach. The fact that TEE is

performed during general anesthesia, may influence myocardial

and valve function, and interpretation should be done with

caution. However, experienced echo cardiographers are aware

of this limitation. A counter effect of checking important items

and offering the opportunity to adapt the surgical plan is that

ad hoc decisions may be taken. Although this risk is present, the

Isala Safety Check is not performed to replace the heart team,

where cardiologist and cardiothoracic surgeon decide together

the best treatment strategy for this patient. However, in the case

of unknown or changed important findings, it may be unethical

to ignore this.

If patients are not informed about the performance of

the Isala Safety Check and the possible consequences and

adaptations of the operation plan, this may interfere with the

consent of the patient. Therefore, it is mandatory to inform the

patients of this checklist and the possible consequences, and to

verify that patients agree with its use. Other items may be added

to the content of the Isala Safety Checklist in the future when the

outcome of the data show that certain adaptations appear more

in specific patient groups. It may be mandatory for these selected

groups to adjust the work up for certain operations in order to

realize a safer surgical strategy. Furthermore, the outcome of the

check is depending on the quality and the interpretation of the echo findings and the culture in the operating room to discuss

the strategy. This necessitates skilled professionals and an

open, respectful atmosphere where everyone’s contribution is

appreciated. A final limitation is that until now the benefit of the

Isala Safety Check has not been demonstrated in a randomized

controlled trial. However, the concept of providing a safer cardiac

operation by applying the check will rise no doubt at all.

With reference to the results of checklists in various fields

where professionals perform high-tech interventions in multi

disciplinary teams, it is our believe that the Isala Safety Check in

combination with monitoring results, discussing complications,

a learning attitude and focus on teamwork will reduce both

mortality and complication rate. Evidence based medicine

is the standard of care, and therefore we advocate a registry

of the implementation of the Isala Safety Check, including the

adaptations to the original operation plan. Many checklists have

been introduced and evaluated. To our knowledge, a randomized

clinical trial has not been published; probably due to fact that

double blinding is impossible.

Surgical checklists have proven to reduce perioperative

complications. The addition on top of the timeout procedure of

a specific checklist for cardio-thoracic surgery may increase the

awareness of the team of potential pitfalls, and enable change

of the surgical approach. The Isala Safety Checklist offers an

opportunity to systematically address specific risk factors and

discuss possible interventions. Timing of the checklist just before

skin incision adds actual cardiac information derived from the

images of the pre-operative transesophageal echo to the data of

the patient’s history, and creates the opportunity to adapt the

surgical plan to a safe strategy. Future research is necessary to

evaluate the added value of the Isala Safety Check in the outcome

of cardio thoracic surgery patients.

For more articles in Open Access Journal of Cardiology & Cardiovascular

Therapy please

click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/jocct/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/jocct/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment