Late-Onset Warfarin-Induced Skin Necrosis: A Standing Shadow-Juniper Publishers

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS-OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL OF CARDIOLOGY & CARDIOVASCULAR THERAPY

One of the clinical situations linked to the use

of warfarin is the skin necrosisoccurring in approximately 0.01 to 0.1%

of all patients receiving warfarin. Typically, lesions develop during

the first days after initiation of warfarin therapy (usually around the

tenth day) and are often associated with the administration of a loading

dose. The pathophysiological mechanisms for warfarin-induced skin

necrosis, despite several theories, remain uncertain. For the diagnosis,

along with a high degree of suspicion, a rapid recognition and

management is required.

Warfarin-induced skin necrosis (WISN) is a

complication of therapy with coumarinassociated with a high morbidity

and mortality [1]. In 1943, the necrotic changes were first time

described on the skinof a patient taking warfarin, at that time it was

called “disseminated thrombophlebitis migrans” [2] and were not related

to the use of warfarin. Later in 1954,Verhagen reported 13 confirmed

cases of warfarin-induced skin necrosis [3]. Overall, these lesions

occur in approximately 0.01 to 0.1% of all patients receiving warfarin

with a predilection for females in up to 90% of cases, beingthe typical

patient a middle-aged, obese, female withhistory of deep vein thrombosis

or pulmonary thromboembolism, with in most cases a reported protein C,

S, Factor V Leiden, and antithrombin III deficiency [4].

82 year old female palestinian patient with a medical

background of diabetes mellitus type II, essential hypertension and

ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (New York Heart Association

Classification grade II), severe coronary three vessels disease

undergoing stenting in coronary descending artery nine years ago and

being a pacemaker holder due to a sick sinus node six months ago. In

addition she was diagnosed a chronic atrial fibrillation two years ago

being on warfarin since then, apart from other drugs to control her

multiple comorbidities. After a period of clinical stability for the

last three months, the patient was admitted in our hospital with a

diagnosis of acute pulmonary edemabeing treated in Intensive Care Unit

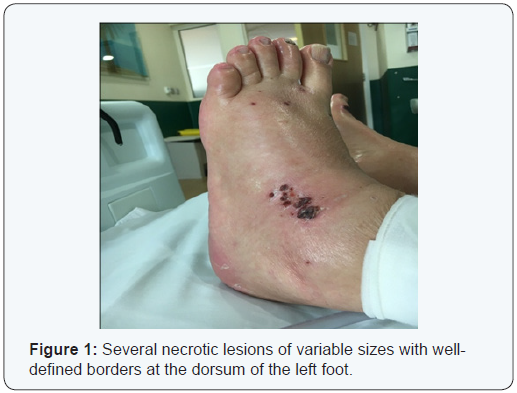

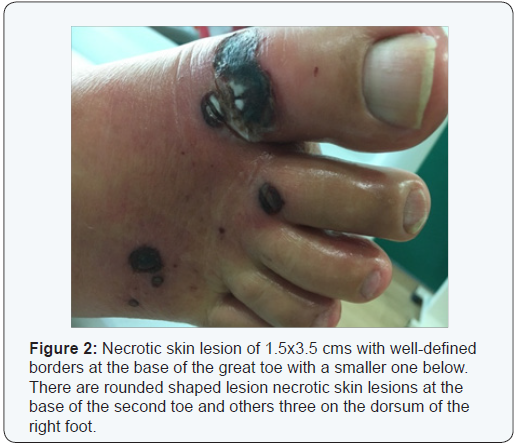

(ICU) with standard therapy. Moreover, upon first physical examination

in ICU were noticed some blisters with red borders filled with what

appeared to be a dark bloody contents on the skin of the dorsum of the

right foot and left footin number of three in each food with a variable

diameter, being the largest of 3 cm of diameter on the right foot and

tenderness upon palpation. After two days, there was a perceptible

improvement in the cardiac status of the patient and was transferred to

medical ward with still mild to moderate edemas in both feet. The

international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.8. The chest x ray showed

mild pulmonary congestion. The electrocardiogram revealed an atrial

fibrillation with normal ventricular response and by transthoracic

echocardiogram the ejection fraction was 35-40 %.

On day fourth of hospitalization, the lesions on both

feet looked like the ones shown in figure 1 and 2 being requested a

consultation with a dermatologist and a vascular surgeon whom after

their assessment stated that the patient was having a WISN. Immediately,

warfarin was discontinued and the patient was started of enoxaparin.

The lesion began to being treated topically with clobetazol in cream. At

that time was requested a blood protein C and S activity that came up

normal days after. After 10 days of thorough observation of the

progression of the lesions, there was an improvement of them indicating

signs of going into remission and with not need of further debridement.

Due to the improvement of the largestlesions after the warfarin’s

withdrawal and the disappearance of those in formation was

agreed not to perform a cutaneous biopsy. Subsequently, upon

discharge, enoxaparin was shifted to dabigatran for home

treatment.

The WISN as a complication of warfarin usage is uncommon.

Typically, lesions develop during the first days after initiation

of warfarin therapy (usually around the tenth day) and are

often associated with the administration of a loading dose.

The pathophysiological mechanisms for warfarin-induced skin

necrosis, despite several theories, remain uncertain, although,it

has been informed to be related with microvascular thrombosis,

hypersensitivity to warfarin and a direct toxic effect of the drug.

However, the most likely mechanism seems to be a temporary

imbalance between the anticoagulant-procoagulant system,

more specifically associated with a rapid decrease in C and S

protein levels during initial therapy with warfarin [5]. Regarding

the lesions associated with this condition, the patient first presents an erythematous rash poorly demarcated and often

associated with tissue soft edemaand paresthesias, subsequently

might appear petechiae progressing within hours to ecchymoses

and large hemorrhagic blisters that turn into afrank necrosis.

In most cases is a single lesion, although, up to one third of

cases can develop multiple lesions. These lesions can develop

at any part of the body, but have a predilection for high fat

areas like breasts, buttocks, thighs, arms, hands, fingers, legs,

feet, face and abdomen. In men, the lesions can affect the skin

of the penis [6]. For the diagnosis, along with a high degree of

suspicion, arapid recognition and management is required. Once

the lesions are recognized, stop warfarin must be the first step in

the treatment, and replace it by unfractionated or low molecular

weight heparin to prevent further thrombi formation. The use

of vitamin K and frozen fresh plasma for a quick replacement of

protein levels C and S is also suggested in these cases, in addition,

the treatment with protein C concentrates is postulated to stop

the progression of lesionsand promotes healing. It is also said

that over 50% of patients might require extensive debridement

and surgical management [7].

The late onset of WISN is very uncommon, few case have

been reported in the literature. However, there are reports of late

lesions onset up to three years after the initiation of warfarin

therapy. It is suspected that late-onset Warfarin-induced

necrosis is a result of poor compliance with Warfarin dosage

schedules, with the patient stopping and subsequently restarting

the medication without heparin coverage [8]. In our patient the

suspension of warfarin and its replacement with dabigatran,

stopped the progression of the lesions which were treated also

with a local steroid cream being noticeable the healing process

over time which took over one month. I would like to stress that

this case might represent another stepping stone to help break

the “old habit” of starting patients on warfarin for long term

anticoagulation-required disease and ponder the possibility of

drugs as dabigatran which has proved to be less harmful in terms

of side effects or use-related complications, besides a faster

onset and offset action, absence of an effect of dietary vitamin K

intake on their activity, and fewer drug interactions [9].

It is not about belittling the old and long live-saving warfarin,

it is about to know who will benefit or harm most when it comes

to begin anticoagulation treatment with warfarin. It is not

infrequent the initiation of treatment with warfarin in patients

who can afford new drugs as dabigatran, but the first choice in

our mind most time is warfarin and no doubts, in some patient

on the long run, warfarin will not do well and the skin necrosis is

like a shadow that always stands and might appear at any time.

For more articles in Open Access Journal of Cardiology & Cardiovascular

Therapy please

click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/jocct/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/jocct/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment