Zero Percent Inappropriate Rates for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention are Achievable and Sustainable at One Year with a Multifaceted Quality Improvement Initiative-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Journal of Cardiology

Abstract

Introduction: Appropriate Use

Criteria Scores for percutaneous intervention (AUC-PCI) are being used

to evaluate appropriateness of procedures performed by hospitals and

interventional cardiologists. Effective strategies for improving AUC-PCI

scores are needed.

Methods: We reviewed all

inappropriate for one year. Multiple interventions targeting the root

causes were implemented. We then evaluated the subsequent percentage

change for AUC scores, prior stress imaging, non-obstructive disease and

PCI volume.

Results: From 2012 Quarter 2-

2013 Quarter 1 (2012Q2-2013Q1) the inappropriate PCI rate was 1.7%;

Following the intervention, there were 0.0% inappropriate PCI for one

year. PCI volume increased by 5.35%; stress testing increased by 5.1%

and the rate of non-obstructive disease increased by 1.5%.

Conclusion: Our experience

demonstrates that 0.0% inappropriate PCI rates are not only achievable,

but can be sustained for one year. Secondarily, there was an increase in

stress testing and PCI volume without a change in the rate of

non-obstructive disease.

Abbreviations: AUC-PCI:

Appropriate Use Criteria Scores for Percutaneous Intervention; PCI:

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; NCDR: National Cardiovascular Data

Registry; ACS: Acute Coronary Syndrome; SCAI-QIT: Society for Cardiac

Angiography and Interventions Quality Improvement Toolkit; CCS: Canadian

Cardiovascular Society; CABG: Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting; EMR:

Electronic Medical Record

Introduction

With the realization that overutilization of medical

services is a critical economic and public health concern, numerous

initiatives have been developed to address the problem. Due to its

widespread use, reducing the frequency of Percutaneous Coronary

Intervention (PCI) has been suggested as a goal [1]. The American

College of Cardiology has been supportive of efforts to reduce

overutilization of PCI in situations where there is limited evidence of

benefit. The Appropriate Use Criteria for percutaneous coronary

intervention (AUC-PCI) were released in 2009 and revised in 2012 to

guide clinical decisions [2]. To support utilization of AUC-PCI as a

quality metric, the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR)

provides AUC-PCI scores in benchmarked feedback reporting. Both private

and public scrutiny has caused AUC-PCI to quickly become an important

performance measure [1,3-5].

The 2012 AUC-PCI guideline divides indications into

three primary categories: Appropriate, Uncertain and Inappropriate. The

NCDR registry institutional outcomes report benchmarks the percentage of

each category relative to other institutions and all registry patients.

Reports are provided for all PCI patients, those with acute coronary

syndrome (ACS) and those without ACS (Non-ACS).

There are numerous challenges to improving AUC

scores. Foremost are the multiple potential causes. These include

documentation deficiencies, errors in data abstraction and variability

in clinical practice [6-8]. To achieve rapid improvement, we implemented

multiple interventions in parallel. This contrast with the traditional

cyclic model of performance improvement where the problem is identified,

a single intervention is planned, implemented and the results analyzed

prior to planning the next intervention.

Methods

To identify causes for inappropriate PCIs specific to our

institution, the NCDR individual fallout reporting feature was

utilized to identify all inappropriate cases for the second quarter

of 2012 through the first quarter of 2013(2012Q2-2013Q1).

The project physician lead (L. Box) reviewed all relevant

documentation. The root cause was identified and entered into

an excel spreadsheet. To develop interventions, we reviewed

recommendations from the Society for Cardiac Angiography and

Interventions Quality Improvement Toolkit (SCAI-QIT) webinar

“Navigating the New 2012 Revascularization Appropriate Use

Criteria” [9], presentations [10], the NCDR quality improvement

for Institutions website and the Accreditation for Cardiovascular

Excellence Cath/PCI standards [11].

Additional solutions were identified through discussion

with all involved providers. The interventions were initiated

beginning in July 2013 and were fully operational by the end of

2013Q4. Presently there is no established standard rate of each

category (A, U and I). The NCDR registry provides reports the 50th

percentile and 90th percentile for all participants for comparison.

We therefore targeted the 90th percentile performance level as our

goal. To better understand the impact on practice patterns, we

pre-specified PCI volume, the rate of pre-procedure stress testing

and the rate of negative angiograms as metrics but without set targets.

A secondary review was conducted to evaluate the accuracy of

documentation specifically related to Non-ACS PCI. Documentation

related to the indication for all outpatient coronary angiograms

for 2013Q1 was reviewed. A determination of the validity of the

stated indication based on the supporting documentation was

made in each case. The key variables as entered into the Cath-PCI

registry were then checked against the documentation to confirm

that documentation and data abstraction was accurate.

Results

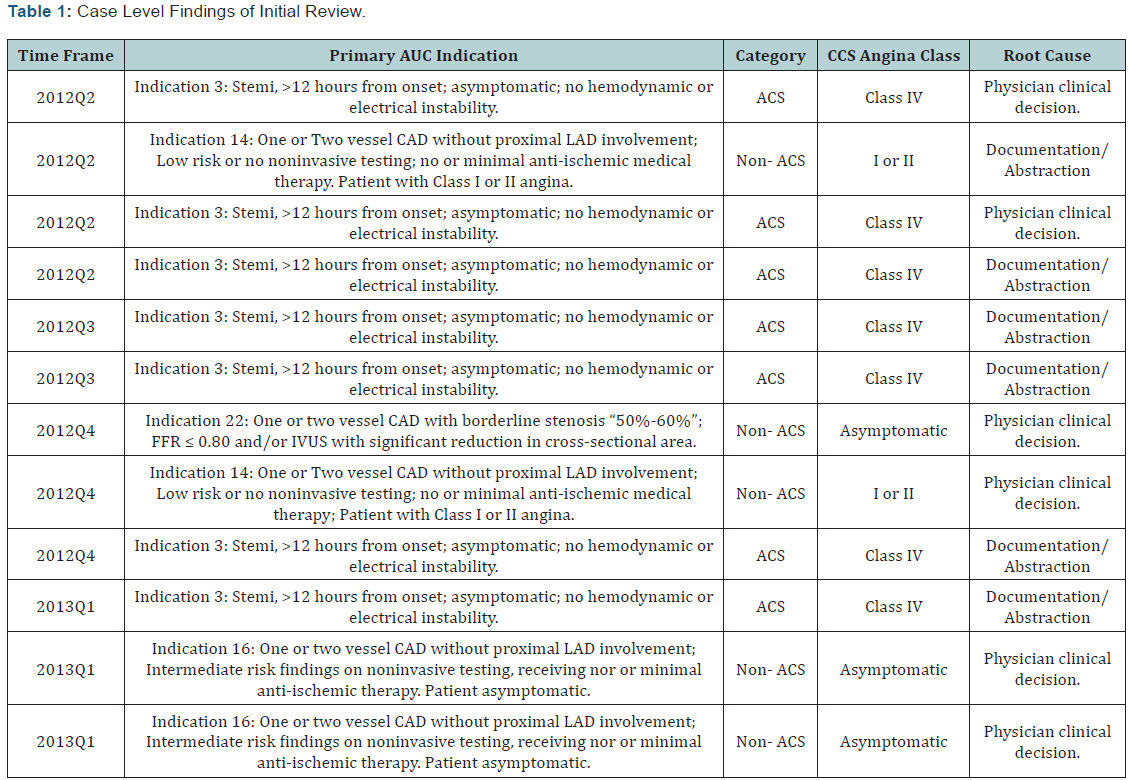

During 2012Q2-2013Q1, there were 12 cases scored I. Of

these, 7 were classified as ACS cases and 5 as Non-ACS. Guided by

the reviewer’s findings two primary causes were identified:

- Physician clinical decision

- Documentation and abstraction.

The second category reflected the difficulty with clearly

discerning the primary indication and clinical history at the time

of abstraction. In general problems with documentation also lead

to inaccurate data abstraction. Therefore, documentation and

abstraction problems were merged into a single cause. The initial

review findings are presented in (Table 1).

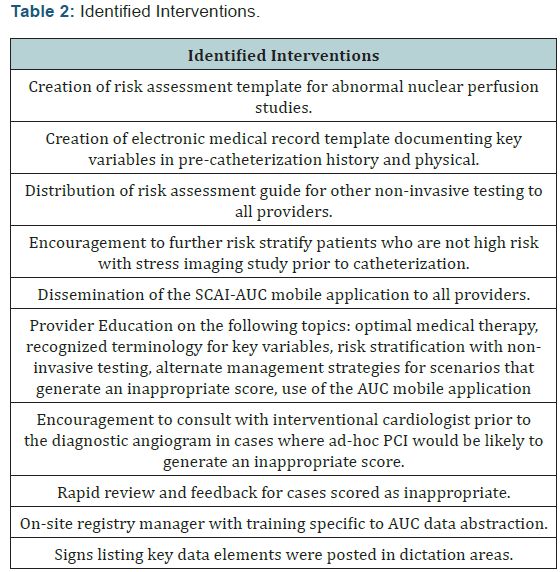

Guided by the chart review findings, we selected multiple

possible interventions for improving performance. These

interventions are listed in (Table 2). A recurring theme across

these interventions was improving documentation of the key

variables for determination of AUC: the Canadian Cardiovascular

Society (CCS) Angina Classification, the number of anti-anginal

medications, noninvasive testing results with a risk estimate and

a prior history of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) [12].

This was addressed not only with templates but also with

provider education regarding the data element definitions and

usage of proper terminology. Education on all interventions was

provided at conferences and physician meetings. To improve

the data abstraction process, a new position was created for an

onsite data registry manager. Previously, data abstraction was

done offsite. The position was filled by an RN with catheterization

laboratory experience (K. Dey). During orientation, the manager

was instructed on the abstraction process relevant to AUC. An

additional challenge identified in discussions was the hybrid

medical record system within our institution. The outpatient

setting utilized the EPIC electronic medical record (EMR) system

while the inpatient setting used paper charts with dictation. To

address this, signage regarding documentation of the key data

elements was placed in all inpatient areas frequently used by

physicians for dictation. All interventions were operational by the

close of 2013Q4 and the project was officially launched as part of

a divisional grand rounds presentation in December, 2013.

Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

The results of our intervention were assessed by performance

on the NCDR Institutional Outcomes Report. Our focus was the

change in the percentage of inappropriate cases as well as the absolute goal of exceeding a 90th percentile performance level.

The additional metrics of volume, rate of stress testing and rate of

negative angiograms were reported as percentages without prespecified

targets.

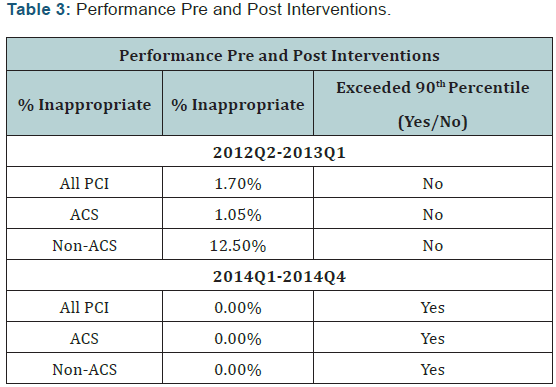

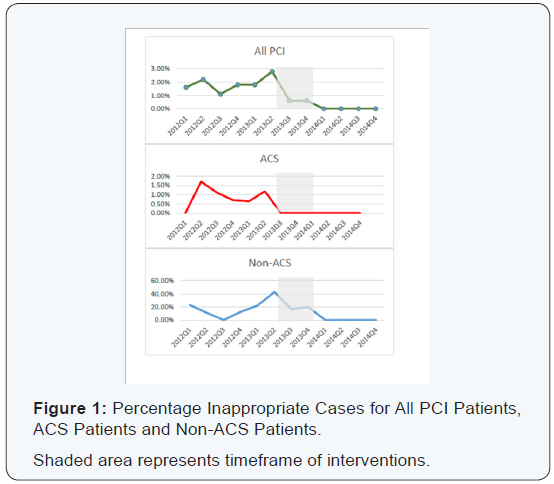

At one year, the rate of inappropriate interventions across

all categories was 0.00%, thus meeting the 90th percentile target

for each category at one full year post interventions (2014Q1-

2014Q4) (Table 3). During the implementation phase, 2013Q2

data had been submitted but was not available. The interventions

were in varying stages of implementation for 2013Q3-Q4. The

trajectory of improvement is presented in (Figure 1) depicting the

quarterly inappropriate score for 2012Q1-2014Q4. The number

of PCI procedures increased by 5.3%. The percentage of patients

with a stress or imaging study increased by 5.1%. The percentage

of patients with non-obstructive CAD increased by 1.5% (Table 3).

Secondary chart review of all elective cases demonstrated 100%

consistency of the stated indication for the procedure with the

supporting documentation. The documentation was also 100%

consistent with the data entry of key variables into the Cath-PCI

registry by the registry manager.

Recent works in this area show the new echocardiographic

methods such as strain rate and speckle tracking echocardiography

to enable easier, more objective and more accurate analysis of the

minimum, initial changes in the function of the right heart, which

will greatly contribute to an easier and more precise diagnosis

and improved treatment of heart diseases in children.

Discussion

Since the introduction of PCI AUC in 2009, hospitals and

physicians have struggled with implementation. One challenge

is the lack of an acceptable threshold. It is not intended that

AUC scores be 100% Appropriate or 0% Inappropriate [12]. At

the hospital level, AUC scores have been shown to have a wide

variation [13,14]. The NCDR registry allows benchmarking

against other institutions with a reported inappropriate 50th

percentile for ACS of 0% and Non-ACS of 13.5% for the 2014Q1-

Q4. Patient level analysis of NCDR data for July 1, 2009 and

September 20, 2010 demonstrated inappropriate ratings of 1.1%

for ACS and 11.6% for Non-ACS [15]. Data from other registries

have found similar rates. Analysis of PCIs performed in the state of

Washington during 2010 found inappropriate ratings 1% for ACS

and 17% for Non-ACS [13]. Examination of the New York State

PCI registry found 14% of Non-ACS PCI scored inappropriate

[16]. In the highly controlled environment of the courage trial,

the numbers were much lower with retrospective analysis finding

only 5.1% of interventions inappropriate [17].

Our experience demonstrates that a 0% rate of inappropriate

is both achievable and sustainable. There have been prior reports

of successful quality improvement initiatives for AUC scores.

Utilization of the SCAI AUC application was reported by both

Chen & Jackson [18,19] as an effective tool for improving AUC

scores. Provider education has also been reported as effective

[20]. A multifaceted approach was described by Beauvallet et al.

& Wong et al. [6,21] but they did not achieve the same degree of

improvement nor did they report sustained improvement over

one year.

Our efforts included the active involvement of a physician

lead and strong engagement of all interventional cardiologists

within our institution. Many potentially inappropriate PCIs were

avoided by informal consultations prior to angiography. Timely

communication between the registry manager and providers

through feedback reports rapidly improved both documentation

and abstraction. Having a dedicated registry manager on site

facilitated this process.

Most of our interventions were voluntary. However, the use

of templates for reporting stress test risk results and for preprocedure

documentation of key variables were adopted by the

division as mandatory. These requirements are likely to have the

greatest impact on AUC performance improvement [9-13]. Use of

the SCAI AUC application was optional but it was adopted by many

providers. The educational intervention addressed variations

in clinical management leading to inappropriate scores. Group

discussion of alternative management strategies for common

inappropriate scenarios reinforced didactic education and

increased provider comfort.

There were likely other factors beyond the

interventions

contributing to the low inappropriate rate. It has been reported

that regional practice patterns of lower utilization predicts lower

scores [22]. In fact this study was conducted in an area with lower

rates of PCI utilization. The Dartmouth Atlas reported 4.4 inpatient

PCI procedures per 1000 medicare beneficiaries for the state of

Idaho in 2012, which is at the 10th percentile [23]. Our lower than

average rate of negative angiograms (Table 3), higher symptom

burden, greater use of two anti-anginal agents and percentage

of high risk stress tests suggests a conservative management

approach across providers. In particular, our negative angiogram

rate suggests good patient selection [24].

Critics of AUC have suggested that procedures based on sound

clinical judgment may be deemed inappropriate by AUC criteria

[25]. This raises the concern that patients might be denied needed

care due to concern over performing an inappropriate procedure.

This was not a clinical study and therefore we cannot exclude this

possibility, however, there were no anecdotal reports to support

this concern. Analysis of the courage trial data suggests that such

events would be infrequent [17]. A possible interpretation of our

success is that documentation did not accurately reflect the true

clinical scenario. Our secondary analysis of all cases for 2013Q1

argues against this possibility.

To verify the validity of this review, the documentation and

abstraction process was also discussed with the NCDR staff and it

was felt that our methods were sound. Physicians were educated

on utilization of terminology that was consistent with the NCDR

data dictionary, but were explicitly instructed against intentionally

misrepresenting the clinical facts to avoid inappropriate scores.

There has been widespread speculation that overutilization of PCI

is driven in part by economic concerns and that implementation

of AUC would decrease the number of PCIs being performed [8].

During this initiative, PCI volumes actually increased. While this

may have been due to multiple factors, it certainly does not support

the claim that AUC will reduce the number of interventions.

Conclusion

Given that providers were encouraged to increase utilization

of noninvasive testing prior to coronary angiography, it is not

surprising that the percentage of noninvasive testing increased.

Interestingly, this did not change the frequency of nonobstructive

disease found at the time of angiography. This could

be interpreted both as a sign that needed care was still being

delivered or alternatively, that the utility of noninvasive testing

in the evaluation of ischemic coronary artery disease is lower

than current perception. The most likely interpretation is that

given the conservative practice style already in existence within

our group, the increase in stress testing had a minimal impact.

It does raise the concern that broad implementation of AUC may

actually increase cost while not improving care beyond what can

be achieved with sound clinical judgment.

LimitationsLimitations of this study include the study design, which was a single center observational study. We cannot make any conclusive statements regarding the clinical effects of our interventions. Future studies regarding the clinical impact of very low inappropriate AUC scores need to be conducted in a prospective, randomized trial. However, given the current available evidence, we do believe it is reasonable for institutions to target the lowest inappropriate AUC scores possible. This report provides an overview of a successful multifaceted approach to reach this goal.

Comments

Post a Comment